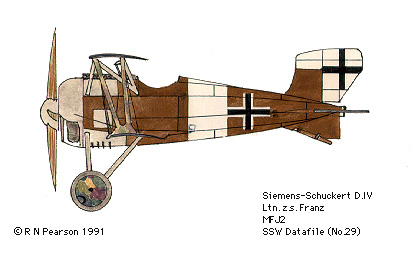

Siemens-Schuckert

Werke SSW D.IV

The Siemens-Schuckert D-IV, coupled with its revolutionary contra-rotary engine, was arguably the greatest German fighter of the war.

Artwork by Bob Pearson.

Historical Notes:

In early 1917, the Siemens-Schuckert Werke developed several prototype fighters to make use of the newly developed 160 hp Siemens-Halske rotary engine. One prototype was chosen as the design concept for what became the SSW D-III. Forty-one of these machines were built and sent to the Western Front in April of 1918 for trials with Jasta 15 of JG II, then commanded by Rudolf Berthold. Berthold himself flew one of the machines, and scored several victories with it, one of them being a Spad XIII on May 29. While Berthold wrote good reports regarding the performance of the plane, especially its superior climb, others seized upon the SSW D-III's tendency for piston seizure as a reason to condemn the entire project. The problem focused on the unique Siemens-Halske Sh-III contra-rotary engine. The Siemens firm had already developed extensive knowledge with rotaries by building Gnome engines under license before the war. By 1914, the Siemens-Halske firm, a subsidiary of Siemens-Schuckert, had fielded their first contra- rotary engine, the Sh-1. The Sh-III was simply a further development of the early war design.

Unlike previous rotaries, where the crankshaft remained stationary and the propellor and cylinders rotated together, the Sh-III's crankshaft and cylinders rotated opposite of one another, with the propellor fixed to the crankshaft. The Sh-III had eleven cylinders, and was rated at 160 hp with each half turning at 900 rpm. In essence, the engine was actually rotating at 1800 rpm, thereby generating tremendous power for its size. But therein lay the Sh-III's troubles. Since the cylinders actually rotated slower than other rotaries (example: the Clerget on the Camel rotated at 1250 rpm), the Sh-III did not get sufficient cooling. Coupled with an enclosed metal cowling, and the acute shortage of quality castor oil, one can see how the SSW D-III could have repeated engine troubles. The lower part of the cowling was cut away to help alleviate this problem, but the castor oil shortage was a constant headache. On more than one occasion pilots flying SSW machines were forced to dead-stick land when their engines seized. Contrary to belief of some, the counter rotation in the engine did not eliminate torque, but it did reduce the gyroscopic effect of that torque.

After being pulled from JG II in June, the modified SSW D-III, now called the D-IV, participated in the second single-seat fighter competition during June and July of 1918. The SSW D-IV was pitted against the Fokker E-V (later D-VIII) monoplane. While the SSW D-IV showed tremendous promise and was better as a high altitude fighter, the E-V was just as good at altitudes below 10,000 feet where the lion's share of aerial combat occurred. The E-V was selected as the primary rotary engine fighter for production, with the SSW D-IV receiving limited orders. While the Siemens machine was superior in many ways, the Fokker aircraft was easier and cheaper to produce, lighter, and demanded a less powerful and proven engine in the Oberusel rotary. Furthermore, the Fokker machine was close to 10 mph faster.

SSW D-IIIs and IVs found themselves being delivered to Jasta 14, MFJ III, and later to Jasta 22. Some also found their way to Kest 2, where they proved themselves excellent interceptors against Allied bombing efforts against German industry at the end of the war. However, production was limited by engine availability, and only about 200 were delivered by war's end (80 D-IIIs and 119 D-IVs). The most powerful version, fielding the Sh-IIIa 200-240 hp engine, was delivered in limited numbers before the armistice was signed in November. Little known to the Allies, the SSW D-IV was arguably the best German fighter of the war, and perhaps the best fighter all-around. Its snap and steady turn rates were excellent, especially the late model D-IV with the Sh-IIIa engine, making it the most maneuverable fighter of the war. Its short fuselage and shallow wings made it nimble in combat, although the controls required constant attention by the pilot, as the plane could easily slip into a spin. Despite its superior abilities, the Allies ignored this type at the end of the war, and production continued up to 1919. Highlighting this point is the fact that Jane's 1919 "All the World's Aircraft" has a single small paragraph on the SSW D-IV, and no entry for the Siemens-Halske engines. Some D-IVs were still in operation as late as 1926.

Construction of the SSW D-IV was of a semi-monocoque design, with plywood longerons and formers enclosed in a 3-ply skin that was then covered with doped fabric. This gave the fuselage considerable strength The wings on the D-IV were of equal chord, the upper wing being of a new airfoil design and reduced in chord from that of the D-III in an effort to limit drag, and thus increase level speed. The wings used plywood spars reinforced with pine, while plywood was used to cover the wing from the leading edge back to the first spar, where it was then only fabric covering. To help improve roll rate, each wing had an aileron. The tail vertical fin was of unique design to help counteract the high torque experienced by the pilot while taking off. All control surfaces were of metal tubing and covered with fabric.

Basic performance statistics: Siemens-Schuckert D-IV (D-IV with Sh-IIIa in parenthesis)

Engine: 160 hp Sh-III; later (200-240 hp Sh-IIIa) both 11 cylinder contra-rotary

Weight: empty 1,190 lbs; loaded: up to 1,620

Maximum speed: 118 mph

Climb rate: to 16,400 ft (5,000m) 12 min. 6 seconds.

Service ceiling: 26,240 feet (one source says 21,100 feet)

Flight endurance: 2 hours

Basic Specifications:

Manufacturer: Siemens-Schuckert Werke (SSW)

Dimensions: Span 27ft, 4.75in; Length 18ft, 8.6in; Height: 8ft, 11in; Dihedral: none;

Areas: Wings 163.25 sq ft

Armament: twin Maxim machineguns synchronized to fire through the airscrew

Typical ammo load: 500 rounds per gun

Primary sources: "Jane's Fighting Aircraft of World War I, 1919 (1990 reprint); "German Aircraft of the First World War," Gray and Thetford; "Fighter Aircraft of the 1914-1918 War," Lamberton, et. al.; "German Air Power in World War I," Morrow; "Aircraft Camouflage and Markings 1907-1954," Robertson et al; "Military Small Arms of the 20th Century," Hogg and Weeks; "World Encyclopedia of Aero Engines," Bill Gunston.

Fighting and winning in the SSW D-IV:

The SSW D-IV is an excellent plane, especially since the version used here is the late-war model with the more powerful Sh-IIIa engine. The climb rate is phenomenal, with the ability to easily and quickly get above any opponent. Its roll and snap turn are the best of any fighter the machine would encounter during the latter part of 1918, while its steady turn allows it to outmaneuver most opponents while maintaining altitude. Nevertheless, the plane can be tricky to fly, and when performing tight maneuvers can take the pilot into a nasty spin. If too close to the ground, it is easy to spin this machine in. When turning, one needs to be careful not to overturn, as the plane will begin to stall out and lose control, and altitude.

Moreover, the SSW D-IV, while a little faster than its close cousin the D-III, is still somewhat slow for the era. Therefore, it does not serve well as an interceptor for faster scouts and two- seaters. Nevertheless, it is an excellent dogfighter, and does well on the Zone when facing others who may have some planes not accurately modeled, and thus better than they should be.

As mentioned before, the SSW D-IV was arguably one of the best fighters of the war.